What is "Religion"?

Discussing Terminology and Holy Scriptures, through a Brief History of Early Hip-Hop

When we talk about ‘Religion’ today, many of us presume quite specific qualities to be at the ‘core’ of it. You need your holy book, you need a defined creed, a uniting, over-arching concept or entity, you need a temple of some kind where your community can gather, you need the community itself, you need ceremonies, and a Master of Ceremony, and very often you need music. While this is obviously no exhaustive list, these are some of the aspects most often associated with “Religion”. But in the case of the above, what then distinguishes Judaism, Christianity, and Islam from, say, American Hip-Hop culture of the late 70ies-early 90ies? Allow me to paint you a picture.

From its inception, Hip-Hop was a community above all, one that emerged from hardship on the ground, and a conflicted, strained cultural landscape. Disco had been dominating the music scene in the late 70ies, but by the early 80ies, with some exceptions, Disco was more or less dead. This was a result of what is often called the ‘Disco backlash’, which, while it may sound silly to people who do not remember it, at times actually manifested as real conflict in the streets. Racist and homophobic motivations behind parts of the Disco backlash are relatively well known, and suffice it to say that not too differently from the heyday of Elvis Presley, large segments of the American population wanted disco gone because it had become a significant domain of expression and influence for black Americans, as well as American gay and trans communities with regards to Disco.

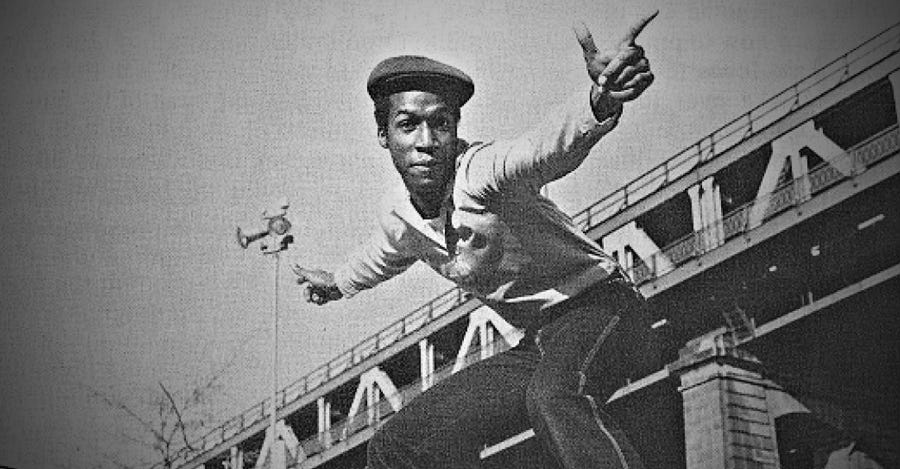

However, a lesser known story is the story of the Disco-backlash within Hip-Hop itself, which in the late 70ies and early-mid 80ies, even well into the 90ies, was predominantly a black, American, New-York based venture. Rather, the Disco-backlash can almost be seen as counter-racist within the Hip-Hop context, although homophobia certainly played a part in the early Hip-Hop community and the backlash against disco as well. But though it was in many ways a reaction against commercialism and the music industry, in Hip-Hop, the Disco backlash was also a sonic backlash. In early Hip-Hop, there was no such thing as records and labels, and if you wanted to experience it, it would be on the streets, in parks, or at a house party, most likely somewhere in the Bronx, Queens, or Brooklyn. That is, you did not find Hip-Hop in the clubs, on vinyl, nor on the radio in the late 70’ies. What you did find was Disco.

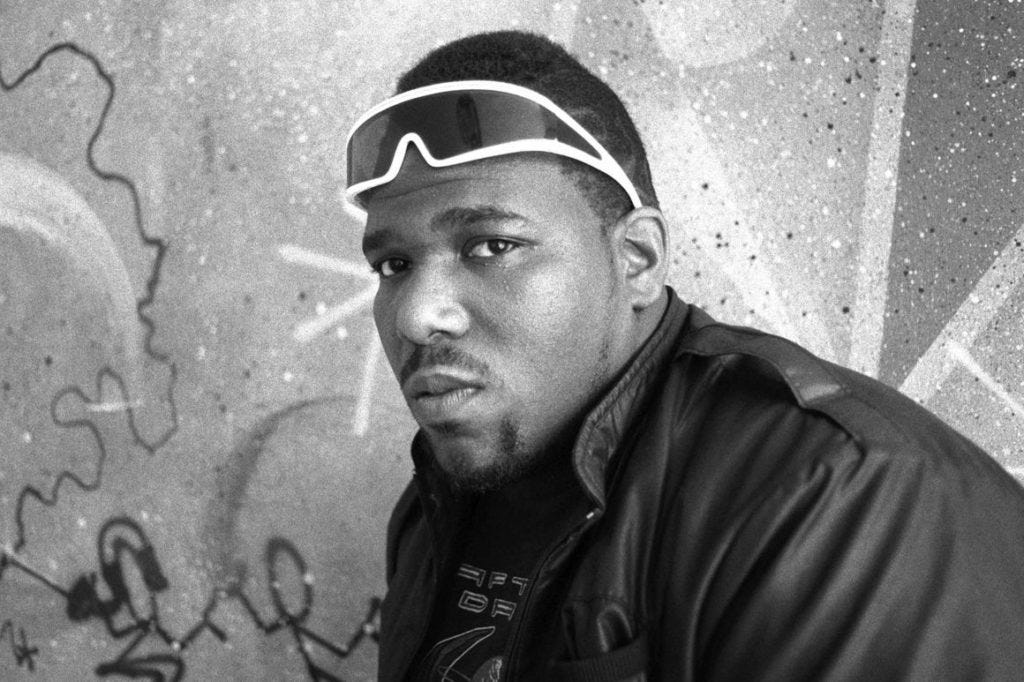

The pioneers of early Hip-Hop, however, names like DJ Kool Herc, Africa Bambaataa, Coke La Rock, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious and/or Fantastic Five (and/or four/five + one), the Cold Crush Brothers, DJ Red Alert and others are often mentioned, were heavily Funk, Soul, New Wave and Electronica-based. It would not be unsurprising to go to a street party in the Bronx in 79 and hear Kraftwerk, the Shadows, Parliament-Funkadelic, and James Brown in succession. However, when people think of early Hip-Hop, their minds often go to a particular number, that is Rapper’s Delight by Sugar Hill Gang. To many of the above names, Rapper’s Delight, which came out in 1980, technically making it the first Hip-Hop record played on radio by some measures (this depends on your definition of Hip-Hop), did not land well in the nascent Hip-Hop community.

Rapper’s Delight was a record label invention (Sugar Hill Records), and even worse, it was Disco. And even worse than that, allegations of stolen rhymes were raised against a member of Sugar Hill Gang, Big Bank Hank, who allegedly stole, or other iterations of “used without asking/crediting the author”, lyrics from Grandmaster Caz of the Cold Crush. While this was not much of an issue for the label, as Caz at this point had been spitting bars on the streets and not on wax, and as such no copyright existed for them to worry about, this was a deadly sin within Hip-Hop. In fact, one of the lines allegedly stolen from Caz, “Don’t ever let a MC steal your rhymes” made the ordeal particularly inflammatory.

Opinions on Sugar Hill Gang remain divided to this day, although they have come to be remembered, also by some “insiders” in the community, for giving Hip-Hop a mass-appeal that it seemingly did not have before. Making Hip-Hop appeal to the masses became a running topic of contention in Hip-Hop, and by the early 90ies, in some circles mass-appeal was associated with “selling out”. For others, Hip-Hop was the epitome of “making it big”, or B.I.G., as it were. To over-simplify vastly, in the mid 90ies, Hip-Hop predominantly came in two flavors: Conscious (East) and Gangster (West). Often outsiders couldn’t tell the difference, and to be frank there was a large overlap (for example, one of Ice T’s greatest inspirations for 6 in the mornin’ is actually the East Coast MC Schoolly D [yes that’s how it’s spelled damnit], specifically the track ‘P.S.K. - “What Does It Mean?”’, and of course the aforementioned Notorious B.I.G., or groups like Wu Tang Clan and Onyx blur the lines delightfully). But this way of seeing it was not predominant within Hip-Hop. On the one hand, we had N.W.A, Dre, the Rhyme Syndicate (which I know Ice T was also part of, I just wanted an opportunity to mention something with Everlast/Eric Schrody) and others on the West coast, with their even more Funk-heavy gangster rap, which was taking the world by storm. On the other, we had “the old guard”, and their new protégés, the jazz-rap, conscious Hip-Hop of the East coast. Well, there was also New Jack Swing but that’s a story for another day.

Suffice it to say, on the East coast, a particular way of thinking about Hip-Hop grew out of the late 80ies and early 90ies. To some, it was snarky and snobby and overly protective of a genre that was reaching a kind of mass-appeal beyond what had been possibly conceivable a decade earlier. To others, its was the Real, the true Hip-Hop. De La Soul, A Tribe Called Quest, Monie Love, Queen Latifah, and the Jungle Brothers, collectively referred to as The Native Tongues, was a collective of Hip-Hop artists with a very particular vision for Hip-Hop. To the Tongues, Hip-Hop was a set of musical traditions that had to be honored, but it was also about consciousness, about a kind of Afrocentrism that had existed since the very earliest Hip-Hop, about women’s liberation, and anti-commercialism.

Many participants took Islamic names (or Islamic-affiliated, there are some uh, let’s say “intriguing” cults to talk about here, such as the Nation of Gods and Earths, but that must wait for another time) to reflect either their family faith, or as a counter-point to the ‘white’/’Christian’/English mainstream. And while I do not have time to go deeply into it here, though Hip-Hop has struggled both with what I would call a kind of Orientalizing of ‘Africa’ in black American communities, and with balancing Afrocentrism and the black, disenfranchised heritage and history with the concept of racial equality, as the scene opened up to white Americans as well as the global music scene, Hip-Hop has always (also) had a strong, universalist nerve within it.

So, with this brief exposition of early Hip-Hop, we return to the concept of ‘Religion’. Today, there are temples of Hip-Hop, founding figures such as the ones mentioned here are venerated in the community, at large, particularly amongst the originals and sub-sets of Hip-Hop participants and enthusiasts that grew from the “Native Tongues school of thought”, which often claim to be the inheritors of the real, original Hip-Hop (since it was New York-based, and many from the “new guard” were directly musically raised by the originals from the Bronx and Queens). In fact, I did not use “Master of Ceremony” at random in the introduction to this essay. While “Microphone Controller” is also recognized by many today, the original (probably, it’s hard to say for certain) understanding of the abbreviation ‘MC’, one still particularly dominant in the Conscious Hip-Hop sub-culture, is ‘Master of Ceremonies’. The term has existed since the very early days of Hip-Hop, and during the 90ies, in New York in particular, it developed into a term used to distinguish ‘sellouts’, or rappers, from the real MCs, representing the true tradition.

In many ways, the history of Hip-Hop is a history of people coming together. Of a struggle (You could say Hip-Hop had a baptism of fire, its entire “childhood” essentially being during the Reagan Era, and it being heavily scrutinized and suppressed even into the 90ies, with cases like against 2 Live Crew, reminiscent of the scandalism and censorship leveraged against Elvis and the Blues, Soul, and Gospel scenes on the 50ies-70ies) to become a community, of that struggle turning into success, turning into institutionalization, internal conflict over originality and heritage, the “true” way of the tradition, and following diversification. If you recall the story of the Three Rings from Boccaccio, summed up in the introduction to this Substack, allow me to put forward a small argument.

The Battle of Interpretation and the Contrastual Mind

The concept of holy scripture, that is, a multi-layered and divine source of knowledge pertaining to fundamental aspects of human life, and legitimized by a community through its antiquity and proximity to the divine origin, is a very old one. The Greek and Arabic words 'exegesis' and 'tafsīr' (ἐξήγησις and تفسير) refer to explaining or leading out something from text (usually). In the Jewish, Christian, and Islamic traditions, these terms have been used to refer to the interpretation of holy scripture, and a plethora of approaches to the interpretation of the Torah, the Gospels, the Qur'ān, Hadīth and many others.

The interpretation of Scripture in Abrahamic religions have led, amongst many others, to the creation of the Talmud, the basis for Torah-study in contemporary (rabbinic) Judaism, the foundation of Christian monasteries in the 3rd century, the Islamic law schools, mystical traditions such as Kabbalah or the Sufi tradition, and the works of the Christian church fathers (as well as the different denominations of Christian churches, which partially come from different trajectories of interpretation). But although this concept has often been employed in the Abrahamic tradition, as we have seen here, the art of interpretation is, of course, not exclusive to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

One thing Abrahamic interpreters had in common, regardless of their religious affiliation, was an approach laid out or inspired by ancient Greek philosophies. In particular, Plato and Aristotle came to have enormous impact, even on what in modern times is often considered absolutely central Jewish, Christian and Islamic doctrine. However, other traditions such as Stoicism would also gain prominence in the intellectual environments and debates of the first millennium AD.

These intellectual environments, and the debates that grew out of them, were not isolated from one another in their particular traditions. Rather, constant theological and philosophical interaction and debate took place between various cults, thinkers and creeds, to the point where it is often quite difficult to draw any hard borders between them. Thus, what we in our time often consider separate, fairly easily delineable boxes of religions, effectively shaped each other into the modern religions we know today for millennia. Does this mean Hip-Hop is a young ‘Religion’? While I’m sure some would say so, it is not the point of this essay. The point here is really quite simple: It is hard, if not impossible, to understand Hip-Hop without Disco, just as it is hard to understand the Talmud or the Gospels without Plato. It is impossible to know if someone means “rapper” as a descriptor or a derogatory dismissal, unless you know their favorite artists, just as it is hard to know what a “friend of God” means without knowing when and where this “friend” is mentioned. You can hardly understand modern Judaism without Maimonides, and you can hardly understand Maimonides without medieval Islam, and you can hardly understand medieval Islam without Aristotle.

It is impossible to know the meaning of “East coast” without “West coast”, as it is to know Christianity without Islam, or Islam without Christianity. Human beings, you and me, we like contrasts, and we like defining ourselves, and others, in contradiction to something else. It is seemingly impossible to escape, though many attempts have been made. But the awareness that this is a tendency we have allows us to get a fuller picture of millennia of human contrast-construction.

I hope, my esteemed reader, that this article has given an impression of the way I will be approaching ‘Religion’. This is by no means meant to be an exhaustive definition of ‘Religion’, maybe it is not meant to be a definition at all. I am not trying to convert you, nor do I work under any pretense that I have exhaustive knowledge in the vast topic that is Religion (or Hip-Hop, or history, for that matter). I am not trying to confirm nor deny the existence of God, or the divinity of Hip-Hop. I am, however, trying to compare human behaviors across time and space, not only because I suspect it will help us understand said behavior, but in terms of ‘Religion’, I suspect that pinpointing what about Religion can be understood as a common human quality, may in one sense make it easier for us to see if any parts of it are not - but more importantly to me, it may help us hone in on how much unites us, and consequently how little divides us.